How to irk your boss and other helpful advice

In-house creatives must be provocative and ambitious, says ex-Oatly creative director Kevin Lynch

The head of school was standing in my office, too furious to sit.

He was the leader of Shanghai American School (SAS), China’s oldest, largest, most storied international school, overseeing an institution with an annual budget north of €100 million and a reputation that was admired as far away as the admissions departments of Ivy League universities. He’d just come from a meeting with a parent group that was up in arms over a recent marketing effort the school had launched.

Standing across from him was his director of marketing who was, well, me – the first director of marketing since the school was founded in 1912. “Since I took this job,” he said, his face red with anger, “no one has been a bigger pain in my ass than marketing.”

It was the nicest compliment I’d ever received.

Because based on my experience, if an in–house agency is going to succeed in doing great work, they’ll need to be ambitious and provocative; to retain their rough creative edges all while pushing boundaries from within. And let’s face it, that’s likely to cause some irritation along the way.

SAS is one of two in–house agencies I’ve helped lead. The other was my most recent role as creative director at the equally strong–willed Oatly Department of Mind Control. (I’ve also worked at over a half dozen ad agencies, but who hasn’t?) As different as Oatly and SAS are as organizations, their in–house agencies shared a few common traits that helped us do great work. Perhaps they can help yours too.

Bus-side campaign from Kevin Lynch’s time in-house at the Shanghai American School

GAIN TRUST FROM THE TOP

When he wasn’t being justifiably pissed at me, the head of school at SAS was wonderfully supportive. He stood by our team as we aggressively worked our way into projects that went far beyond ads to create new touchpoints, cultural artifacts and rituals, and even student programs. (One advantage of an organisation that goes 104 years without a director of marketing is, no one knows where the boundaries are supposed to lie.)

The same trust was found at Oatly. Founded in the mid–90s, Oatly was reborn in 2013 under the partnership of CEO Tony Peterson and his longtime friend and creative director, John Schoolcraft. Today, Oatly is one of the world’s most distinctive brands, and it earned that accolade by breaking rules and ignoring how a brand is supposed to act. During each controversy John and his team created along the way (and there were a lot), Tony had his back.

The byproduct of having trust and respect from the top was that it established an inspiring environment where people felt the freedom to experiment and make mistakes. More importantly, it enabled a streamlined approval process: The people tasked with making the work are the people entrusted with approving the work.

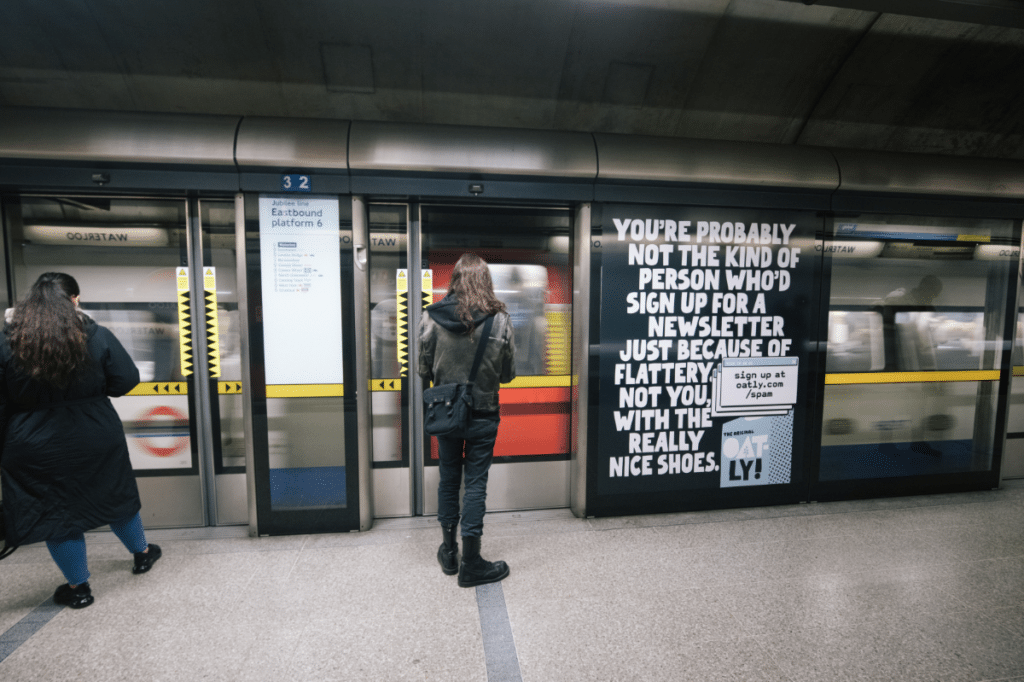

Oatly newsletter campaign

DON’T TAKE BRIEFS, MAKE THEM

The relationship between ad agencies and clients has a well–entrenched master–and–servant lexicon – to the point where people working on the brand side lose their personal identities and simply become “the client.” There’s no reason for this hierarchical thinking to exist, period – and certainly not with an in–house agency.

At both Oatly and SAS, we were not referred to as an “agency” and other members of the organization were never considered our “clients.” On the contrary, we were respected as the marketing experts we were and, ultimately, it was up to us to decide what was promoted and how.

At Oatly, if an upcoming product innovation wasn’t something we thought was particularly interesting, we would either ignore it or we would do a campaign that made fun of it. (Ironically, this approach would always endear us to more people than if we took on a more predictable praising tone.)

That doesn’t mean we worked without collaborating with other organization leaders, or that we lacked an understanding of business objectives and upcoming initiatives. It just means we took requests for marketing initiatives as suggestions, not dictations.

Because we understood how brands are built. And we knew that, at times, our most impactful work didn’t start with a formal brief tied to a rational strategic objective. It started with someone saying, “Wouldn’t it be funny if…”

BEING REACTIVE CAN BE CONTAGIOUS

The upside of being in–house vs. at an ad agency is that you’re fully immersed – not just in the brand, but in the whole organisation. That’s also the downside.

Because now, you’re right down the hall from an executive who just saw a negative tweet about the brand, or heard a rumor about a campaign a competitor might soon be launching, or who is worried about how a recent world event might affect an upcoming in–store event in a completely unrelated market.

It’s easy to get caught up in a world that demands immediate reaction. It’s also easy to not.

At both my in–house roles, we eschewed the temptation to be guided by the whims of real–time data and didn’t fall for the pressure to establish KPIs for every individual initiative. Instead, we treated goals and success measures as destination signs rather than mile markers. (Think annual benchmarks like net promoter scores or broader behavioural insights that could guide a year’s worth of efforts such as, “peoples’ attitudes about sustainability are shifting faster than their actions… how do we close the gap?”)

These longer term “North Stars” not only allowed us to sidestep getting stuck in reactive mode, they also created the opportunity to execute some of our more remarkable projects.

For example, at SAS, we researched, wrote, designed, and coded 167 different stories about the school so that we could turn each of our buses into unique storytellers. At Oatly, we created a global multimedia campaign promoting a newsletter about an oat milk.

Measured on their own, these seemingly absurd projects would not produce particularly impressive ROIs. But the efforts weren’t designed solely to gain short–term attention. They were designed to build fame which has heightened the visibility of everything the brands have done since.

TO SUMMARISE: CHANGE EVERYTHING

Maybe you have an ideal situation already.

Maybe, as the leader of your in–house agency, you have so much trust with your CEO, you don’t run creative work by them (or anyone else) as anything more than an FYI of what you’ve already decided.

Maybe you and the team would never think of your coworkers as “clients” regardless of where they sit on the org chart, and maybe you’ve earned the right to truly control what initiatives you’re going to prioritize and support.

And maybe you’re the one who’s established how your success will be measured, and that you chose metrics that help your team remain proactive, not reactive.

If so, fantastic and please accept my apologies for wasting your last three minutes. But from my observations, the in–house agency experiences I had at Oatly and Shanghai American School were incredibly unique – and these commonalities were essential to creating space for our teams to do work that people loved.

And by “people” I mean everyone except that parent group in Shanghai.

Kevin Lynch is a former creative director at Oatly. He recently founded The Wrong Agency, a creative consultancy that probably no one will ever hire